By S.D. Peters

A Moonshine Romance

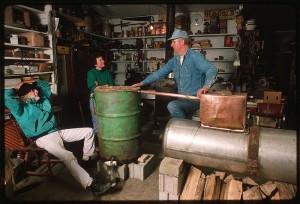

“Moonshine” – a word that’s worth a thousand pictures. Whether sepia-toned, awash in cinematic midnight or muddled with shadows, those pictures evoke a giddy infatuation for Appalachia’s hills & hollers or a longing nostalgia for Chicago’s speakeasies in the hearts and minds of those who have never tasted moonshine, never visited Hazard or Harlan Counties, and were born decades after the Prohibition-era speakeasy’s last call.

The romantic idealization of moonshine’s illicit qualities and dark places has been partially responsible for the growing interest in the product that’s less colorfully billed as white whiskey, but often marketed as “legal” moonshine. Such marketing has annoyed lexicon-minded critics (who’ll remind you that “moonshine” refers to any illegally manufactured liquor, not just whiskey). It may also displease some genuine ‘shiners, for whom moonshine is more than just a living, but also a closely guarded tradition. Then there’s the sticklers who’ll remind you that if you want unaged grain liquor, there’s grain-neutral vodka. According to any of these people, real whiskey’s got to be aged before you can call it a finished product.

Debating whether or not most of what gets labeled moonshine these days is the wrong debate. This type of spirit’s popularity among today’s Scott Favor-ish hipsters – who are so far removed from the days when being hip was synonymous with Bohemian poverty, Beat poets, Times Square hustlers, or Baudelairean junkies – also unfairly leads to suggestions that it’s a fad that’s just a terminal “e” away from obscurity. Calling it moonshine may be inaccurate, but it’s possible that once the hipsters move on, the product will stick around. Yesterday’s trends are often the predecessors of tomorrow’s new traditions.

White Whiskey & Micro Distillers

The trend toward independent micro-distilleries during the past decade is one that I hope establishes (if it hasn’t already) a new tradition – and one that offers a healthy competition with the established big distilleries. The arrival of white whiskey as a high-end commodity is tied to these micro-distillers, for whom unaged liquor (along with small barrel aging) can sustain their young business through the early years spent awaiting the maturity of an aged stock.

The rub, of course, is selling a product that in the established whiskey trade and to many whiskey drinkers looks unfinished. Or would be, but for the interest of whiskey enthusiasts.

Enthusiasts v. Drinkers: Is there a Difference?

Whiskey enthusiasts aren’t your average whiskey drinkers, which is not to say enthusiasts and drinkers don’t share an above-average passion for the product. Drinkers might care passionately about whiskey, albeit only the particular brands or types to which they are loyal. That Jack Daniel’s guy down at the corner bar or the suited single malt sipper who scoffs at blends are typical of whiskey drinkers. They know what they like – and hey, it’s whiskey, so who’s to argue except perhaps a teetotaler? Certainly not me, the guy who always keeps a bottle of Wild Turkey 101 Straight Rye Whiskey and Black Grouse on hand.

What makes enthusiasts different is that they aren’t decisively sated, if they’re ever sated at all. Whether constantly ISO a new experience or gradually evolving their taste, they’re more likely to experiment – and lately, that experimentation has led some of them to white whiskey.

Enthusiasts… or Elitists?

On the surface, an enthusiast may not seem too far removed from elitism – and contemporary hip-dom, which has taken to white whiskey, does tend to conflate the two – but buttonholing all enthusiasts as hipsters or cultural elitists is no better than assuming every whiskey drinker is a low-brow alcoholic.

The closest I get to hip is sitting beside someone on Metro (a very bad joke that proves my point), but my taste in whiskey has evolved (or maybe just changed) over the years at a rate comparable to trend-seekers, even if it’s always a generation or two behind. From Jack Daniels to Makers Mark; Johnnie Walker Black to The Ballvenie Doublewood 12 Year; Wild Turkey 101 Bourbon to Old Overholt to Wild Turkey 101 Rye; and lately, to Knob Creek Rye, small batch ryes like Thomas H. Handy Straight Rye, and the blended peatiness of The Black Grouse; my taste has progressed from sugary sweet to spicy smoke.

These days, I prefer experimenting with whiskeys that have the latter characteristics, but I’m still discovering whiskeys that remind me sweetness isn’t always a bad thing – discoveries I’ve mostly made in offerings from micro-distillers.

The Right Debate: Tasting the Grain

White whiskey offers a new tasting experience, and although I prefer to call the product clear whiskey (a more literal name that avoids elite panache and the “unfinished” stereotype), I’ll accept whatever name helps a larger audience get to know it (even if that name is “moonshine”). There may be no better way to taste the distilled grains – the base of all whiskey – without the multiple risks that may accompany the sampling of an unregulated, untaxed home-distilled version of grain alcohol made by some guy don’t know, and sold to me by some other guy I don’t know.

White whiskey is a finished product, insofar as it’s sold and bought as such, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s still the foundation of what’s usually called whiskey. In the amber liquid, redolent of caramel and vanillin, or the golden stuff rich in the flavor of Highland smoke and peat, the grain, tempered by the aging process, lends abstract characteristics to the finished product. The crisp spiciness of rye, corn’s syrupy sweetness, and barley’s earthy flavor; those are the notes of grain in the symphony of aged whiskey.

Without aging, white whiskey offers a chance to experience the grains’ raw flavors. As found in white whiskies from upstart distilleries like FEW, Catoctin Creek, or Troy & Sons, distillers who specialize in the evolving art of white whiskey are finding ways to reduce the sometimes unpleasant intensity of clear whiskey’s high alcohol content, and elicit a right grainy goodness.

But How Far Can It Go?

The white whiskey experience may convince enthusiasts of the evolving variety that there’s still a good reason why the grain’s flavor should be abstracted in a “finished” whiskey, and I can’t say I won’t agree. How much variety can white whiskey embody without the benefit of wood? How long will it take to determine that, yes, distilled corn tastes like distilled corn, distilled rye like distilled rye, etc.?

I can’t offer an answer to these questions right now, but as I continue exploring white whiskeys, I expect I’ll find them. In the meantime, I prefer to think that the art of whiskey will continue evolving, thanks to distillers who are willing to not only experiment with (and even alter) finished whiskey’s traditional qualities, but aren’t afraid to get down to the business of exploring raw whiskey’s defining ingredient: the grain.

Going Forward: Grading White Whiskey

As the Whiskey Reviewer pursues white whiskeys, a question looms: Can white whiskey can be graded the same way as aged whiskey?

Color is obviously not a factor: in the bottle these whiskeys resemble water. In the glass, it’s the same, save for a mild density that’s revealed with a simple swirl. The aroma, flavor, and finish may offer subtle differences, not unlike a finished whiskey in which such subtleties lurk between, say, the caramel tobacco of a finely aged bourbon or vanilla pepper of a rye. Somewhere under the dominant graininess small differences may reveal themselves – the grassy notes in FEW White Whiskey or the smokiness of Wasmund’s Rye Spirit for instance.

There remains the difference of age, and in that there’s really no comparison between an A-grade aged whiskey and an A-grade white whiskey. Both are top-class among their own kind. I expect that distillers who carefully craft their white whiskey can reveal the finer qualities of unaged whiskey, just as a distillers who carefully age their whiskey can bring out the finer qualities in their bourbon, rye, Irish Whiskey or scotch.

Here’s to looking forward to new discoveries!

The Whiskey Reviewer A World of Whiskey, Poured Every Weekday

The Whiskey Reviewer A World of Whiskey, Poured Every Weekday

Sorry, just not my cup of tea. My vote: unfinished.

Some people like green wine too, but not me.