By Richard Thomas

If any premium bourbon brand name has achieved true crossover fame, departing the realm of whiskey enthusiasts and entering popular culture at large, it is Pappy Van Winkle. So great is Pappy’s renown that I am periodically contacted by past acquaintances (in one instance, the last time I saw or spoke to this person was in grade school), who, having learned I’m an established whiskey writer, seek my help in securing a bottle of the fabled liquid.

Alas, they are out of luck. For even were I inclined to pull favors for someone I haven’t spoken to in 20 to 35 years, I just don’t have that kind of pull. Whenever I’m asked about it, what I always say is a person should find and cultivate senior management at a big retail liquor chain or at a distributor, because those are the only outfits who receive enough bottles that they might pass one on to a charming newcomer for the sticker price.

Yet as Pappymania marches on into 2017, it’s worth asking if the emperor is still wearing all of his clothing. Does Pappy deserve all of the spotlight focused upon it, especially in view of the fact that it now occupies the center of an ever more crowded stage of very old, super premium bourbons.

How Did Pappy Get So Popular?

The cornerstones of the Van Winkle brand’s stardom are happy serendipity and relative scarcity. To understand these dual factors requires a quick lesson in modern bourbon history.

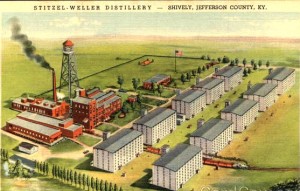

Since the early 1970s, Van Winkle Bourbon was a brand without a distillery, made under contract for family patriarch Julian Van Winkle II (Pappy’s son) at the Stitzel-Weller Distillery in Shively, a suburb of Louisville, Kentucky. This timing coincided with the world whiskey bust, which left traditional producers around the world sitting on an ocean of whiskey nobody wanted to buy. Stock sat in the rickhouses for longer, including the Van Winkle stock, which would lead to many of the age statement whiskeys that emerged a decade or more later.

Julian Van Winkle II died, his son Julian III took over, and Stitzel-Weller itself closed in 1992. Until 2002, Van Winkle was primarily sourced through Bernheim Distillery (owned by first Brown-Forman and then Heaven Hill during that time), when the brand found its current home at Buffalo Trace.

A lot of happy accidents had to come together to make Van Winkle whiskey the superstar it is today. First, a combination of production factors (mash, yeast, warehousing, etc.) enabled Stitzel-Weller to produce an excellent wheated bourbon, one that continues to be (ever more) dearly prized by bourbon aficionados to this day. That bourbon aged well (not all bourbon does), and the world whiskey bust ensured there would be enough sitting on the ricks year after year to start bottling very old expressions. Pappy Van Winkle 20 Year Old was introduced in the early 1990s, around the same time as the Jim Beam Small Batch Collection (Knob Creek, Booker’s, Baker’s, Basil Hayden).

Finally, there was never very much Van Winkle bourbon in the first place. The annual autumnal release has hovered between 7,000 and 8,000 cases for many years now, and it will be several more years before that number expands appreciably. Scarcity combined with top rated stock from a defunct distillery to create a certain mystique. Moreover, when bourbon first started attracting real attention again just over a decade ago, Pappy Van Winkle was one of the few brands that had those attention getting, very high age statements on the label.

Is The Pappy Mystique Still Justified?

A simple exercise in math tells us that if Stitzel-Weller closed in 1992, the last of that prized juice should have been expended in Pappy Van Winkle 23 Year Old in 2015. Given that the Van Winkles haven’t suggested that any of their stock has been stored in stainless steel tanks (as Buffalo Trace did with Eagle Rare 17 Year Old), freezing it in time, it is very likely that the older Van Winkle whiskeys are now based squarely on Bernheim stock, not the original and much-prized Stitzel-Weller bourbon, with Buffalo Trace stock percolating into the lower entries of the line.

That Bernheim wheated stock from the 1990s has a good reputation, but it’s not the stuff of legend in the way the Stitzel-Weller whiskey has become. Also, Pappy Van Winkle now stands amid a field crowded with aged bourbons, such as Elijah Craig 23 Year Old or George T. Stagg 17 Year Old. There are even ultra-aged bourbons from lost distilleries around, such as 2016’s Parker’s Heritage, a 24 year old bottled in bond bourbon made at Heaven Hill’s old Bardstown distillery, destroyed by a fire in 1996.

So, unless you are a diehard enthusiast for wheated bourbon in particular, Pappy Van Winkle should now be just another face in the (admittedly prestigious) crowd, yet it remains strongly overpriced. The 20 Year Old routinely fetches between $1,500 and $2,000 a bottle, and the 23 Year Old between $2,000 and $2,500 a bottle. By contrast, Elijah Craig 23 Year Old can be had for $300 to $400; George T. Stagg 17 Year Old for between $500 and $800; and Parker’s Heritage 2016 is available for $600.

Since some of the reasons for Pappy Van Winkle’s fame are no longer valid, and you can buy between three to six bottles of comparable super premium bourbon for the same amount of money, the brand is clearly coasting on hype. Yet given that just a few years ago, suggesting (incorrectly at the time) that W.L. Weller 12 Year Old was “Baby Pappy” was enough to cause a run on the brand name that continues to this day, Pappy has more credit stuffed away in the bank than the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund. Hype will carry it for a long time to come, but as is the case with long running TV shows, its glory days are already over. Pappy van Winkle has already jumped the shark.

The Whiskey Reviewer A World of Whiskey, Poured Every Weekday

The Whiskey Reviewer A World of Whiskey, Poured Every Weekday

Didn’t Buffalo Trace tank the Sazerac 18, not the Eagle Rare !7 as stated in your article?

I jumped the gun. Doing further research, it looks as if the ER was tanked as well.

Yeap, both were tanked.

Isn’t your thesis based on the theory that, because the current juice is not from the old Stizel-Weller reserves, it doesn’t deserve the accolades and interest? While much of the Pappy fame was a product of the bourbon that came from the S-W bottlings, it seems that this is sort of irrelevant. What matters is whether or not the current product meets expectations, regardless of where it is produced. Moreover, any product can be improved and, while it might sound blasphemous to those who follow the hype, it is possible that conditions at another distillery could be such that they produce an equal or even superior bourbon to that which came from S-W. Your secondary point, about other super premiums that are now available, sort of alludes to this. I’m not arguing that Buffalo Trace makes a better product. I’m saying taste and quality of the product are fundamental. Everything else is ancillary.

The hype behind Pappy is to a large extent driven by emotion, and that is certainly the case now when so much of what made it popular in the first place is no longer anywhere near as true as it once was. The thing is that the hype will go on despite that, because most of the people driving that hype have never had and will never have any experience with the original aged, S-W wheated bourbon so responsible for all this.

IMO, the Bernheim and Buffalo Trace wheaters also used in Pappy are both excellent, but S-W had a certain magic going on. It’s that tiny little bit of extra something that separates the very good from the great.

FYI: Harlen Wheatley has told me since this was written (and apparently hasn’t said so on the record anywhere else, because if so I’ve never seen it) that some S-W juice still goes into Pappy 15, 20 and 23. That strongly suggests they socked some away in stainless steel containers.