No, Bourbon Bros: A Trade War Won’t Put Blanton’s Back On Shelves

By Richard Thomas

When I penned Why The Trade War Didn’t Put Pappy Back Within Reach in December 2021, a year after Joe Biden’s clear victory in the 2020 elections, I never expected to revisit the subject of tariffs on American whiskey exports again. But here we are.

The trade war started by President Trump in his first term had already left a sword dangling over the collective head of the American Whiskey industry, in the form of a 50% European Union tariff that was suspended, but not repealed after Biden took office. That 50% import duty on American whiskeys is due to take effect on March 31 of this year, and seeing as how Trump is talking more, not less conflict over trade, the prospects of an extension or reprieve look dim.

As if that were not bad enough, Trump’s obsession with tariffs seems likely to trigger still more retaliation against the American whiskey industry. Trump only recently chickened out of starting a trade war with two of America’s biggest trading partners, Mexico and Canada, but without giving up on his obsession with tariffs. After postponing blanket tariffs on America’s neighbors, Trump came around to reviving his original tariff project, abandoned as a failure after his first term: a 25% duty on imported steel and aluminum, plus new retaliatory tariffs to match any duty placed by any country on American products.

As part of forcing Trump to back down, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau threatened to put a tariff on imported American whiskey. Canadians even ran out ahead of him on this issue, with stores boycotting American whiskeys and taking bottles off the shelves.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons — Inu Etc/CC by 4.0)

In the background of all this international news were bros with podcasts and Reddit croakers, who responded to the news that Canada was going to smack a tax on American whiskey imports with joy. Many of the same people had an identical response in 2018, when the EU put a 25% tariff on American whiskeys in response to Trump’s original tariff on steel and aluminum and made the threat to raise it to 50%. Their claim was those darn foreigners would not pay higher prices for American whiskeys, so all that Pappy, Taylor and Weller would come home, where their listeners and readers could buy it! Despite sales of US-made whiskey falling in Europe by 20% before Biden could arrange relief in 2021, their fever dream scenario never happened.

Whiskey producers were hurt, as predicted, and many in the craft sector were saved from bankruptcy only by a surge in drinking and sales during the Pandemic, but the predicted return of the “good old days” never came about. Then as now, the Bourbon Bros are wrong, both about the economics and about how the whiskey business works.

Why Target Whiskey?

When the EU targeted American Whiskey in 2018, it was widely perceived as a pressure move against then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. Most of the whiskey in question was Kentucky bourbon, a key industry in McConnell’s home state. Canada had a similar idea in mind with its threatened retaliation, openly declaring they would target exports from Republican-dominated states and key Trump allies: Kentucky is the country’s top whiskey state, with equally Republican Tennessee coming next. Indiana is, if anything, even more Republican than its southern neighbors, and also home to MGP, the supplier of most of the industry’s aged stock whiskey so valuable to sourced brands.

But beyond being a targeted measure designed to pressure certain Red State politicians, targeting whiskey makes economic sense as well, because it is unlikely to have direct negative consequences for the country in question. Liquor is a luxury item with plenty of width and depth. For most consumers around the world, if a 50% tax is slapped on Jack Daniel’s, they’ll probably just buy Johnnie Walker instead. A tariff of this kind is unlikely to drive inflation or cause pain on domestic consumers in the way taxing necessities would, but merely push down sales of the targeted item. At the same time, bourbon’s loss is a net positive for Canadian, Irish and Scotch whiskies.

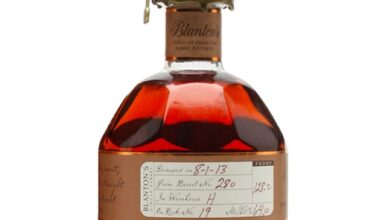

(Credit: Richard Thomas)

Trade Wars Won’t Put Blanton’s Back On Shelves

While it is true that the EU’s 2018 tariffs depressed sales of American Whiskey inside the trading bloc by a substantial margin, what the Bourbon Bros are choosing to ignore (twice!) is which sales were effected. Left untouched were the sales of the top shelf brands so passionately sought by enthusiasts. Instead, what suffered were mass market products that have never been in short supply in the States. The reason why is known to everyone who has ever taken an Economics 102: Microeconomics class in college.

People who want to pay $2,500 to buy Pappy Van Winkle 15 Year Old on demand have substantial disposable incomes, and if they really want that Pappy, they are not going to blink at paying $3,750 (+50%) for it instead. The same can be said about paying $200 for a bottle of Blanton’s or $250 for W.L. Weller 12 Year Old, despite their official prices being far lower. Those who can pay such prices already are, and tacking another $100 onto the price tag will not deter them. They are already paying a premium for these things, and with the disposable income on hand for such individuals, the real question is not “if” but “how often.”

However, raising the price on a bottle of Elijah Craig Small Batch from $35 to $50 has a different effect, because that is not perceived as a pricey, luxury purchase. That is an every day item, and as the meme “But but the price of eggs” prove, the public responds to price increases on every day items with hostility. Just as people are always willing to pay a premium (if they can) for a luxury good, they demand bargains for more ordinary things.

(Credit: Joana Thomas)

Yet even if raising prices by a quarter or half on all the Blanton’s shipped overseas caused its export sales to dry up and Sazerac decided to bring all its Blanton’s home, the event still would not do very much to put Blanton’s back on shelves in the way that it was present a decade ago, and the reason is simple numbers. We don’t know the actual statistics, but let’s assume 10% is destined for export (I suspect 10% is a large overestimate). Obviously, 90% of all Blanton’s is already in distribution in the US, so bringing that small fraction home would not really change the domestic supply all that much. Recall this is an item with an MSRP of $65 and a market value of $281. That supply and demand imbalance implied by those numbers is not going to be resolved by such a modest increase.

Bourbon Bros show their true colors in their eagerness to believe conspiracy theories, blame foreigners, ignore inconvenient facts and wish for things that would badly hurt the industry they claim to love. They will never acknowledge the reason they cannot buy Blanton’s is themselves. 43 million Americans drink bourbon, a number rivaling the entire population of Spain. If even a tiny fraction of that number were counted as enthusiasts, that still leaves vastly more mouths chasing popular brands than what can be produced by those brands. Hence, those brands will be substantially marked up, taken off shelves and put into locked display cabinets. That is how the free market works.

The truth so eagerly ignored is the reason so many limited editions are both expensive and difficult to find is not just found at home, but is sitting in the room with us. As just illustrated, the US has more drinkers in its domestic market than the whole population of a medium-sized country. The American whiskey industry looks at exports as a hedge against a downturn in domestic sales, not their bread and butter. Making whiskey companies put the few eggs they were trying to sell in another market back into the one basket, no matter how large that basket may be, does not make the price of eggs cheaper. What it does do is make those companies more vulnerable when the basket gets bumped at the market.

Bourbon bros destroyed my bourbon club.

About a dozen years ago, I started a club with a couple of friends. One passed away and the other moved away, so it was just me running it after about six years. Around that same time, we got more and more of these dudes who were all Barstool Sports or Joe Rogan, if not drooling MAGA. They chased out the not-bro and women members, just by being unpleasant douche canoes. I finally gave up too. The club folded within a year of my quitting. The bros couldn’t run a club to save it and its very well-established perks for themselves. It’s not just Don the Con who turns everything he touches into sh*t.

I stopped reading this article because I can barely read.

So typical. Everything their cult leader wants gets spun into some fantasy.