Jim Murray Says Bourbon Tops Scotch. Is He Right?

By Richard Thomas

Jim Murray, the Englishman who pens the annual Whisky Bible, stirred up enormous controversy in whiskey circles last week when he was quoted by The Telegraph as saying scotch whisky was now being outdone by American whiskey.

“Generally speaking, bourbon … has overtaken scotch” said Murray. “The best whisky is coming not from Scotland any more, but from Kentucky.” He went on to label Buffalo Trace as “arguably the best distillery in the world.”

Murray specified one particular problem for The Telegraph, namely that many of the old sherry casks used to mature scotch are treated with sulfur candles first, leaving a bitter finish behind them. He also pointed to the widening use of caramel as an additive. Murray’s growing affection for Buffalo Trace in particular is an open secret in industry circles, especially after he awarded two expressions from the distillery’s Antique Collection the No. 1 and No. 2 slots in the Whisky Bible 2013.

Comments like those from a renowned expert were guaranteed to spark outrage, particularly in the British media and among British whisk(e)y fans. As I well know, there are plenty of Britons for whom that one little “e” is a matter of heresy rather than semantics, so the notion of “whiskey” topping “whisky” rankles them. However, as one who grew up in the midst of bourbon country, moved to Europe, and later came to embrace scotch, I have my own thoughts on the matter.

Bang For Your Buck

One of the points on which American whiskey beats scotch whisky hands down is cost, and that holds true whichever side of the pond you are on. Let’s take Knob Creek, the classic small batch bourbon from Jim Beam that gave some serious momentum to the revival of premium whiskey in the United States. A fifth of Knob Creek (750 ml) tends to run about $35 in the U.S. At nine years old, Knob Creek is a middle-aged bourbon, and costs about the same as Glenfiddich 15 Year Old, but far less than Balvenie Doublewood ($47) or a 12 or 15 Year Old Macallan ($45 to $90).

The same price differential holds true in the UK, where a 700 ml bottle of Knob Creek usually costs £35, but is sometimes available for £30 or less. Being in the UK merely means the Balvenie Doublewood costs about the same as Knob Creek, and the Doublewood simply isn’t as good in the first place. Comparable single malt or blended Scotch almost always costs more. The price gap between bourbon and scotch narrows in Britain, but it doesn’t close.

This point becomes even clearer at the very top of the scale. The two whiskeys Murray favored so much in his 2013 Whisky Bible, the 2012 Thomas H. Handy Rye and William Larue Weller Bourbon, both retailed for only $70. True, Buffalo Trace rations its Antique Collection whiskeys, and long waiting lists have become a fixture in acquiring both these and the more expensive Pappy Van Winkle bourbons. However, it remains the exceptions to the rule for even super premium bourbons to fetch the kind of prices routinely associated with the equivalent scotches.

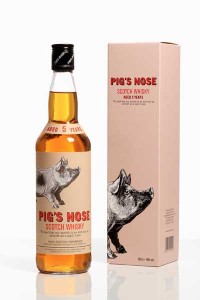

Even so, there are some scotch labels that offer good quality at reasonable prices, especially among the blends. Spencerfield Spirit’s Pig’s Nose and Sheep Dip are usually available in the U.S. for $30 and $40 respectively, and are much cheaper in the UK. Monkey Shoulder and Scottish Leader offer even more reasonably priced alternatives to the mass market blends, as does the recently revamped Black Bottle. Finally, while not quite up to Knob Creek standards, classic single malts like Glenfiddich 12 Year Old deliver good value wherever you are.

(Credit: Spencerfield Spirits)

The Subjective Side

If the price tag attached to a whiskey bottle is objective, taste is subjective, as critics of Murray’s views are eager to point out. “Caramel and sulphur sticks do not damage the whisky. This is really about Jim Murray’s personal taste” said Rosemary Gallagher, spokesperson for the Scotch Whisky Association. Many would agree with that statement.

While my own experiences with tasting American whiskey and Scotch whisky has led me to the conclusion that if you put a bourbon (or rye) next to a single malt of equal quality, the American one will almost always come out as the better buy in sheer price terms. Also, mass market American whiskeys are generally a bit better than their Scottish equivalents (Jim Beam vs. Johnnie Walker Red anyone?).

Yet I also think that Scotch whisky has a wider, deeper range than bourbon, rye, or bourbon and rye put together. If between 40 and 70% of the flavor of a whiskey comes from wood, scotch has a rich array of wood choices for maturing its spirits, whereas whiskey in America relies on the one general format: toasted new oak. Compared to scotch, that constrains American whiskey somewhat, and I think the best proof of that is in how the Scottish idea of barrel finishing has spread to the U.S. Those aging differences help make even American malts different from what most in Europe do, making comparisons a tricky business.

This point comes back around to Murray’s belief that American whiskey has overtaken scotch whisky. His opinion is pinned on wood maturation, and his preference for new oak over sulfur-treated sherry casks. Those wooden differences underscore what makes for an odd comparison in the first place, and while not quite a matter of comparing apples and oranges, it is certainly like comparing apples to pears.

As you say, it’s a price-point thing for many consumers, while also ultimately being a subjective taste for whatever you may like more.

So is bitter pleasurable objectively to the human palate? Or is Jim Murray just correct all together?