How The Wood Makes Whiskey Good

Exploring The Types Of Whiskey Oak

By Richard Thomas

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Whenever the subject of why a given whiskey tastes the way it does arises, my favorite statistic is that, depending on who made it, barrel aging contributes between 40 and 80% of the flavor. Barrel aging itself breaks down into several factors, but the oak used in making that barrel, cask, butt, hogshead or pipe is of clear importance.

Underscoring just how important oak is to maturing whiskey is how the different types of oak each have their own particular influence on flavor. The world is home to over 600 species of oak tree, but only a handful are currently in use by whiskey-makers around the world.

American White Oak

Whether it be bourbon, rye, malt or Tennessee whiskey, the bedrock of American whiskey-making is new Quercus alba, or white oak. Once cured, toasted and charred, this oak provides the vanillin, lactone and wood sugars that give American whiskeys their characteristic caramel and vanilla flavors, as well as their amber color.

Chris Morris, Master Distiller at Woodford Reserve, said, “These and other compounds will be extracted by the spirit as it penetrates up to half the depth of the oak barrel stave and heading during maturation. Over the many years that Woodford Reserve is matured in the barrel, it will extract on average 85% of these desirable heat derived oak components.”

Remember that statistic of wood giving whiskey 40 to 80% of its flavor? Aging in white oak provides “Woodford Reserve with 100% of its color naturally, and approximately 50 to 60% of its aroma and flavor,” said Morris.

One interesting development that has come out of the craft whiskey movement in America is the use of unusual, regional white oaks, such as what Few Spirits does in relying on oak from Minnesota. The shorter growing season of Minnesota, relative to more traditional cooperage timber areas such as Ohio or Alabama, makes for a tighter wood grain. While this doesn’t change the elements the whiskey derives from the wood, it should slow the process of extracting those elements.

European Oak

Until this year, European oak meant one of two types: Spanish and French. Both are frequently consolidated into the single species Quercus robur, but that simplification isn’t entirely accurate.

(Credit: Pernod Ricard)

“Three main species of [Spanish] oak can be used in cask making,” says Kevin O’Gorman, Master of Maturation at New Midleton Distillery, makers of Jameson. “The most common would be Quercus robur, followed by Quercus petraea and finally, Quercus pyrenaica.”

In Ireland and Scotland, Spanish oak is prized as the wood used in aging sherry, which is then reused for making whiskey. The flavor derived is sometimes simplified as being just the result of the previous seasoning with sherry, but the cask wood itself makes an important contribution.

O’Gorman explained, “American oak contains higher amounts of odorous compounds such as vanillin and oak lactones than European oak. On the other hand, Spanish oak contains more total extractables and particularly twice the amount of extractable phenols than American oak.” This combination of native Spanish oak flavors and seasoning with sherry contributes the dried fruit, nut, fig and date flavors characteristic of sherry wood-aged whiskeys.

Even in the case of French oak, the simplification to just the one species of oak tree isn’t accurate, as Quercus sessilis sometimes appears as well. In the Irish and Scottish context, French oak typically indicates a used wine cask, but some small forays have been made with Scotch and American whiskey using new French oak. Combined with a wine seasoning, French oak can contribute ripe berry flavors and enhanced spiciness, while the use of new French oak (such as in The Spice Tree or Maker’s 46) is known predominately for the latter quality.

“In general, French oak has a good, tight grain structure and is favored by many wine producers in France,” says O’Gorman. “We observed higher levels of whiskey lactones from the French oak in comparison to Spanish oak. We also established that there were slightly higher levels of syringic acid, vanillin, syringaldehyde and coniferylaldehyde due to the French oak contribution.”

One new type of European oak has joined this traditional pair, and that is Irish oak. New Midleton launched a new expression this year partly aged in new Irish oak. As in the United States, this should prove but the initial foray into the use of regional, non-traditional timber.

Where Irish oak differs from its Spanish and French cousins is in that it is exactly the opposite of the Minnesota white oak described earlier. Ireland’s mild, wet climate make for an expansive growing season, giving the wood a wider grain and making it less dense and more porous. These factors accelerate the extraction of flavor elements from the wood, a feature that when combined with Irish oak also carrying more of many of the desired chemicals makes the wood something of a “super” whiskey oak.

Japanese Oak

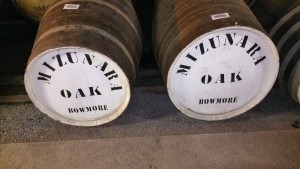

Quercus mongolica is usually referred to as Mizunara oak within the industry. The wood is now found in Scotland as well as Japan, starting with Bowmore making a Mizunara-finished whisky. Currently the Scots follow the Japanese practice relying on their native oak for finishing, due to Mizunara’s specific characteristics.

(Credit: Kurt Maitland)

Japanese oak is particularly soft and porous, so much so that it lacks the sturdiness of other kinds of oak and staves of this wood are prone to leaking. However, the wood is also heavily laden with vanillins, and combined with its wide open structure (recall the Irish oak above) make it a very flavorful wood.

Even as a finishing wood, Mizunara is “subtle, but has a big impact on the final blend,” says Mike Miyamoto, Suntory’s Global Brand Ambassador. “It has tastes of sandal wood, spicy, even cinnamon like flavor.”

Is It The Wood That Makes It Good?

Even at a distillery that says 80% of what its whiskey tastes like comes from the cask, it’s not so simple as to quote Kenny Rogers and say it’s the wood that makes it good. Just with the cask itself, elements such as the size of the barrel, time, climate, and the warehouse the casks rests in all contribute to that 40 to 80% number. Yet when the range of how much time served in the barrel contributes to flavor starts at nearly half, the choice of oak and how it is used are at least as important as any other factor in whiskey-making.

Fascinating. Just the kind of thing that every real enthusiast should want to know about.

As a Scotch master for a Scottish American society I am currently writing a text for a tasting presentation that I will be giving next month which will be featuring six Scotch whiskies that use First Fill Bourbon barrels. The above information has been quite helpful to me, thank you.