The Changed Rules Of World Single Malts

How The Rise Of American And World Malts Have Changed The Fundamentals

By Richard Thomas

Until the advent of the World Whisk(e)y Boom, malt whisky has been a pretty stable category. The overwhelming majority of malts were made either in Scotland or in countries pursuing their own variants of the Scottish model (most notably Japan), a fact best signified by how widespread the spelling “whisky,” sans the “e,” is. Irish malt whiskey was made on similar, albeit not identical lines. The Canadians didn’t do malt whisky, it was made in just a handful of traditional countries, and the category was moribund in the U.S.

Until the advent of the World Whisk(e)y Boom, malt whisky has been a pretty stable category. The overwhelming majority of malts were made either in Scotland or in countries pursuing their own variants of the Scottish model (most notably Japan), a fact best signified by how widespread the spelling “whisky,” sans the “e,” is. Irish malt whiskey was made on similar, albeit not identical lines. The Canadians didn’t do malt whisky, it was made in just a handful of traditional countries, and the category was moribund in the U.S.

None of those things are true today. Malt whisky-making has spread across the globe now, and although most of the newcomers follow the familiar Scottish model, some do so in places with climates that require a serious rethinking of tried and true production methods. An even bigger wrinkle is the revival of malt whiskey in the United States, where it is seen as the next big thing in the burgeoning American craft distilling sector.

Because the Scottish model was so prevalent for so long, it used to be possible to think of all malt whisky as being bound by familiar Scotch-based rules and concepts. That is no longer the case, and viewed from a global perspective, malt whiskey is changing in two big ways.

Because It’s Not All From Scotland Or Ireland, It’s Not All Made In A Pot Still

Scottish and Irish law required malt whisk(e)y to be made in a pot still, and the Scottish style is to use two linked pot stills (the wash and spirit still), while the Irish use a set of three. Because of this, malt whiskey has been inseparable from the pot still, but no longer.

(Credit: Penderyn)

In the American malt whiskey scene, malt whiskeys do not have to be made in pot stills, and in actual practice are made in column (Coffey) stills, pot stills and hybrid stills (i.e. mixing elements of pot and column in one design). Also, the Welsh distillery Penderyn uses a Faraday still, which is a type of hybrid. Malt whisk(e)y made without a pot still will surely become more common in the future.

It’s Also Not All 100% Malted Barley Anymore

Unlike still design, not using 100% malted barley in a malt whiskey is strictly an American thing (at least thus far). Federal law requires a mash bill of 51% malted barley, in the fashion similar to the other major categories of American Whiskey. Some American distillers make 100% malted barley whiskey, but others do not. Since many countries do not have laws requiring 100% malted barley, the idea of using mixed grain mash bills may catch on elsewhere. Prime candidates for such experimentation include, the Dutch and Australians, who are already making Rye Whiskies, and may find their way there.

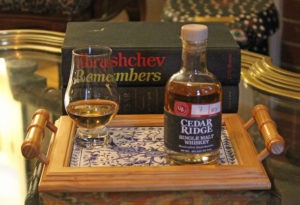

All Single Malts Are Aged In Wood, But Not Always For A Minimum Of Three Years

This rule is a foundation in Ireland and Scotland, and is present in countries where whisky laws exist and were modeled accordingly. Once again, the United States has its own very different legal requirements, and a minimum age is not one of them. American law specifies minimum age periods for the designations “straight” (two years) and “bottled in bond” (four years), but not overall. Likewise, many newcomer countries do not have specific whisky laws mandating minimum aging periods, although the customary three years is observed in an effort to cater to the tastes of Scotch whisky enthusiasts.