Whiskey Fungus: That Perpetual And Pesky Problem

Whiskey Fungus Has Been Around For As Long As Spirits Have Been Aged, And It’s Only Going To Get Worse

By Richard Thomas

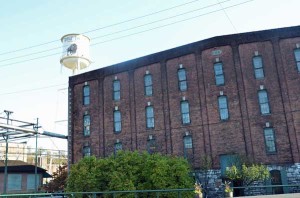

(Credit: JLPC/Wikimedia Commons/CC by-SA 3.0)

Earlier this year, whiskey fungus got back into national headlines, this time in Lynchburg, Tennessee. Even though the 35,000 residents of the rural Lincoln County love Jack Daniel’s Distillery, in the way that one can adore their biggest employer and tourist draw, at least some residents have apparently had enough of the black fungus that accompanies whiskey distilling growing all over the outside of buildings in the county.

Stories of this type are a regular feature of whiskey news, and the black fungus itself is nothing new. Baudoinia compniacensis is a type of fungus that feasts on alcohol vapor, and because the stuff is heat and light resistant, it can be found growing on the outside of buildings all around wherever spirits are stored, as well as other kinds of infrastructre and even plants. A whiskey rickhouse, which could hold over one hundred thousand gallons of high proof liquor, is constantly evaporating alcohol. If it isn’t moving and it is next to a whiskey warehouse, more than likely the fungus will take root and make that thing look dingy.

This evaporation is often called the Angel’s Share, but alcohol vapor is heavier than air, so it disperses at what could be described street level rather than up into the atmosphere. It would be better to call it the community share, rather than the Angel’s Share. That is because if there is enough vapor or the distillery’s warehouses has neighbors, those neighbors will get an unwelcome share of the dirty-looking fungus.

(Credit: Joana Thomas)

Shively, the suburb of Louisville that has long been the urban center of the bourbon industry, has been coated with whiskey fungus for so long that many lifetime residents simply take it for granted. Shively is like many communities with a whiskey fungus problem, though, which is to say that at least some of the people living there are taking the whiskey companies to court over the fungus.

The fungus isn’t harmful to humans, and doesn’t do any damage to structures beyond the purely cosmetic. Treatment with bleach solutions or cleaning with pressure washers takes care of the fungus problem, at least temporarily. It’s also a long establish nuisance that accompanies aging spirits wherever they can be found. What has changed, at least insofar as whiskey in America is two-fold.

First, more spirits are being made in the US that ever before, so the major distillers of Kentucky and Tennessee are building ever more warehouses for storing and aging their whiskeys. That means more vapor, but perhaps more importantly, more vapor in areas that had never seen it before. In Kentucky, you might find a complex of bourbon rickhouses under construction down the road from a commercial retail zone or a residential suburb. In a major city, perhaps that old disused factory has had part of its space turned into a whiskey warehouse by the craft distillery located in the next neighborhood.

The other reason is the same issue, but working in the other direction: people moving into places where the whiskey warehouses already were, and then discovering the fungus problem a few years later. To see how both problems interact, one should simply drive around Anderson, Franklin and Woodford counties in Kentucky. Six large and mid-sized distilleries are found in this area, and as much as the bourbon industry has boomed there, so has the local population. Woodford County was already an exurb of Lexington, and the last decade has seen the population grow by 7%. Franklin and Anderson counties have had growth rates in the lower teens over the same period.

(Credit: Bernt Rostad/Wikimedia Commmons/CC by 2.0)

Federal law is clear that a distillery can vent evaporating alcohol into the atmosphere, so there is nothing technically polluting about this issue. That still leaves a distilling industry open to civil actions due to damages, however.

Even though the fungus doesn’t eat through wood, stone or vinyl, and isn’t harmful to people, home owners might still have a legitimate grievance in the form of reduced property values. I would argue that if you move into a brand new suburb next to an existing whiskey distillery, your gripes about the dingy fungus on your house should be directed at the developer behind the project for not informing you about a relevant defect. But if a distillery builds a rickhouse next to your home, and you suddenly need to start pressure washing it every few years to keep the fungus under control, then you might have a case.

Some distillers in other industries rectify their alcohol emissions with the use of a thermal oxidizer, which eliminates the vapor. However, estimates suggest installing one of these systems on a typical Tennessee or Kentucky rickhouse would cost $400,000 each. I suspect we won’t see the whiskey industry adopting this technology until doing so becomes cheaper than paying out settlements or judgements, and the whiskey fungus lawsuits are all on just square one or two.