Six Laws That Made American Whiskey

By Richard Thomas

Whiskey Rebellion

(Credit: Public Domain)

Whiskey is a quintessentially American drink, a connection that becomes clear when one sees how interwoven it is with American history. The story of American Whiskey is the journey of a rough, unaged distilled spirit made by farmers because it was cheaper to move than grain or flour growing and maturing into today’s modern, multi-billion dollar industry servicing markets around the world.

It’s a complex, multi-faceted history, replete with famous, sometimes legendary figures who are the namesakes of the biggest brands, as well as obscure industrial barons who were perhaps more important than Evan Williams or Elijah Craig. It’s a story marked by both crime and war on the one hand, and genteel Southern mythology, innovative chemists and earnest yeoman farmers on the other.

One way of telling this story is through the law, because few things in real, practical life are as inevitably and tightly bound together as liquor, law and taxation. From that perspective, six events shaped American Whiskey as we know it today.

The 1791 Whiskey Tax

America’s first embrace of that inevitable, tight bind between liquor and taxes came with the passage of the 1791 Excise Whiskey Tax, a measure sponsored by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton as a means of financing the country’s national debt. It was also an early example of a now all-too-familiar theme in American tax bills, namely heavy favor shown to a special interest. Founding Bankster Alexander Hamilton made sure the terms of the excise tax favored large, industrial distillers (such as President George Washington, then perhaps the country’s biggest distiller), while slighting small distillers.

Frontier farmers were not amused, and in Western Pennsylvania resistance to the law spiraled into outright insurrection. The Whiskey Rebellion fizzled when Washington called the bluff of the tax evaders and mustered a militia army, but many of these farmer-distillers chose to migrate from Western Pennsylvania to Kentucky and *temporarily) escape the taxman. Thus, the beginnings of Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey tradition pollinated the creation of Kentucky’s bourbon whiskey.

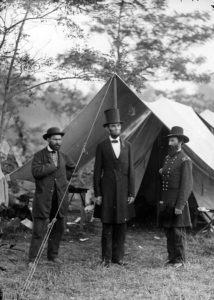

on whiskey to pay for the Civil War

(Credit: Public Domain)

Honest Abe Taxes Distillers

Thomas Jefferson repealed the whiskey tax in 1802, which was then revived briefly to help pay for the War of 1812, before being repealed again. For almost five decades, there was no Federal tax on distilling spirits.

That changed in 1862, when Lincoln reintroduced excise taxes on distilled spirits and wine to help fund the Civil War. From that point forward, so long as Americans were making whiskey, the making part was taxed by the Federal government. As a rule those taxes always went up; any effective reduction in taxation on whiskey came as a result of inflation eroding the real value of the tax rather than a tax cut. In fact, the only Federal tax cut the manufacture of whiskey and other distilled spirits has ever received was under the tax bill passed in 2017.

The Bottled In Bond Act

The late 19th Century was the era of robber barons and Progressives, and one of the things the latter were trying to force the former to do was make sure the food and drug items on the market were safe. The whiskey industry was one sector where the giants of the business embraced, rather than fought, the spirit of the Progressives. Led by Colonel E.H. Taylor, they sponsored the passage of the Bottled in Bond Act of 1897.

Most bourbon enthusiasts are familiar with the provisions of this act. Any whiskey bearing the designation must: 1) have been made at one distillery in a single distilling season; 2) be aged under in a government-supervised warehouse; 3) be at least four years old; and 4) be bottled at 100 proof.

The measure was envisioned by big distillers making quality products as a way of protecting their brands and status against cheap imitators. At a time when what, exactly, bourbon whiskey was had no real legal definition, it was a key first measure in establishing consumer standards.

(Credit: Public Domain)

Taft Improves The Pure Food And Drug Act of 1906

Another Progressive measure was the Pure Food And Drug Act, which forbade the adulteration or mislabeling of any liquor, but didn’t define what those liquors were. President Taft improved on that in 1909 by defining whiskey as a distilled spirit made from grain. He went on to define bourbon as being made from a mash of 51% corn for the first time, as well as that it must be distilled to no higher than 80% ABV and aged in charred, new oak barrels.

Although often thought of as a middling president at best, it was William Howard Taft who codified the cornerstones of what defines bourbon whiskey today (and, by extension, rye, wheat and malt whiskeys as well). Taft began legal definitions for whiskey that continue in the provisions found under Title 27 of Federal law today. That is why he was inducted into the Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame in 2009.

America’s Greatest Failed Social Experiment

Unfortunately for Taft, his groundbreaking codification of what whiskey was and what it was not came at a time when the perception that alcoholic beverages were a social evil was gaining ground. Kansas outlawed alcohol in 1881, and many of the same Progressives whose zeitgeist gave us the Bottled in Bond and Pure Food And Drug acts were also diehard teetotallers.

This moral crusade against distilled spirits (principally whiskey) changed America in ways that remain widely unrealized today. To make national Prohibition possible, anti-alcohol forces supported the passage of the 16th Amendment in 1913, making a permanent income tax possible. At the time, excise taxes on alcohol were a major source of Federal government revenue, so replacing it with the income tax was a crucial step forward in banning alcoholic beverages altogether.

(Credit: Public Domain)

National Prohibition was enacted by the ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1919, and subsequently repealed by the 21st Amendment in 1933. The greatest effect of the Prohibition years, followed as they were by the continuing Great Depression and the Second World War, was a huge disruption of the American Whiskey industry. When Prohibition was enacted, some distillers chose to bide their time and await repeal, while others were convinced repeal would never come and got out of the business. Later economic disruptions ensured that some of the reopened distilleries and some newly founded distilleries failed. By the 1950s, the American Whiskey industry was a very different creature from what it had been in 1918.

The National Spirit

On May 4, 1964, Senate Concurrent Resolution 19 was adopted by the U.S. Congress, declaring bourbon “a distinctive product of the United States.” This resolution has been mythologized into a declaration that bourbon was “America’s Native Spirit.” That would come later, but 1964 was an important step in that direction. It gave bourbon the same protected status as cognac and champagne enjoy in France or Scotch in Scotland: bourbon could be made in America, and only in America. If someone else made a whiskey and called it bourbon, the government would go to bat against them.

Bourbon became “America’s Native Spirit” in fact some 43 years later, when Kentucky Senator Jim Bunning introduced a different resolution. The same act declared September “National Bourbon Month.”